BLOG

50 WALKS

Saturday 17th August 2019

Booker Down Rough/West Harting

I often hear about, read about, and say, that to allow oneself to be vulnerable is a good thing. Brene Brown writes about vulnerability, and gives plenty of evidence in her books which I love to listen to. Recently, I’ve been experiencing it.

A woman and small dog wandering alone out in the woods, slowly.

Would you say that she was vulnerable?

I feel it. I walk tentatively, acutely aware that I’m stepping in to the world of others.

Of other humans and their tracks.

Of other creatures and their trails.

Of the gracious and familiar standing figures with leaf laden branches.

Of spirit.

It’s a bit like walking into a pub on your own, that isn’t your local. You can ham it up with bravery and self-congratulations ‘Look at you, enjoying yourself on your own’. Or you can acknowledge the size of the vulnerability, allow yourself to feel it as you step over the many different thresholds in life, taking part, tasting life.

Noticing this, today I decided to walk a new route, in an unfamiliar place. After much time in a map, following the pathways of the ordnance survey with my finger and eyes, Monarchs Way, South Downs Way, West Sussex Literary Trail, New Lipchis Way, I see that there are two different tones of green for forests. One is a lime-green, the other a blue-green. The first gives public access to the whole woodland, ie you don’t have to stick to the footpaths. Brilliant! I can wander. I found the nearest place to me and made my way there with drawing materials, the dog, chocolate and tea. My staple back-pack. Oh and a biodegradable dog poo bag – just in case. In the blue-green forests the public is requested to stick to the footpaths.

As I walk up Booker Down Rough track I enjoy the pink and green wild flowers that dominate the edges of the bridleway, covered in honey bees, butterflies and flies. I look them up in my book.

Hemp agrimony – leaves opposite, with 3-5 lanceolate, toothed segments.

Broad-leaved willowherb – stem branched in upper part and covered there with glandular hairs. Leave lanceolate to elliptical, toothed;

There is a language to identifying plants, and at the back of the book a guide to the leaf shapes with painted botanical studies to visually describe the terms. Carl Linnaeus created the binomial system for plant identification, in which he categorised plants using hierarchies that gave each plant (or animal) a genus or family name, and a species or individual name, both in latin. With this he gave a language for identification. It required recognition of shape, colour, pattern, scale, similar to the elements that form the language of art.

There is also a language to flowers, some from folklore, for example with the giving of flowers where each flower gives a message to the recipient through what it symbolises. There was a language in terms of how flowers were presented, the Victorians were keen to follow this.

https://www.almanac.com/content/flower-meanings-language-flowers

The Seed Sistas are herbalists, on one of their walks we learned another language of identification, using the smell, flavour and texture. They combine their knowledge of traditions and sciences, for more information: https://sensorysolutions.co.uk/.

But what is this walk about right now?

Is about art, or plants?

‘Language’ came clearly to mind.

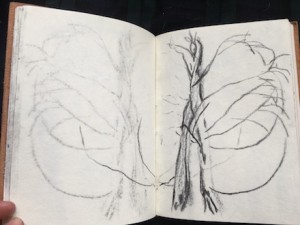

This week I’ve had studio time to develop the drawings from walks into paintings. The language of my practice taking shape in a different medium, and the focus consolidating in my mind as much as on paper. There is a clear style to my work that comes from the process of making it. I realise, with relief, it’s not contrived. It’s not pretty. It’s not conveying pretty thoughts. But it evolves with a language of it’s own. A language that is tangible. It speaks to me.

In the middle of the path in the midday sun

I pause

Focus

On the intention for this walk – in this place

Reflecting on the language of my practice, and asking for access and welcome into these wild woods, that I might be guided by what I encounter

pause again

a dark bottle-green butterfly flies towards me, then into the woods.

I walk on knowing that I can wander into the woods at any point. Soon I find a dent in the growth on the bankside to the left, it gives us way. It is narrow, and a dollop of fresh horse dung indicates it’s a used route. From hot sun, Jack the dog and I are back in the familiar chill stillness beneath tree canopy. As reassuring as it is to have free access, as I walk up the slope I find myself balancing the flower book, sketchbook, glasses and phone, a handful of mis-matched objects that I juggle as my needs change: read this, draw that, record this, etc. Wouldn’t it be great to make something that would organise and hold all this stuff? Getting organised doesn’t take away the ability to improvise and interpret on the hoof, it adds to it. My bumbling hands agree. Preparation is good thing, a helpful thing.

Preparation in my studio is about surface, layering the paper or canvas with an underneath, a textured base layer, or watercolour, and the charcoal, pastel, paint creates the overground. The paintings evolve much like the walk. I start, put something on the page, add another media and then remove some in parts. I create pathways and traces in the undergrowth. The more work I make, the more I am aware of this language and the shape that the marks and textures make.

I’m interested in spirit, and ideas of form and formlessness have been present throughout all my work, and underpin the latest series of paintings. In form and formlessness there is connection, I relate this to the human condition, to our interconnectedness, interrelatedness, to how we/I relate. To the relationship between different types of marks or gestures, different colours and textures, and what I learn from the work once it has evolved.

Different ideas and thoughts form a palette too, that allow the work to evolve as it does. There is a constant state of revolution taking place, with materials, movement, walking, of feeling, observing, noticing. Making the art is like living life, it certainly makes me feel more alive. I feel very grateful for the experience and skills.

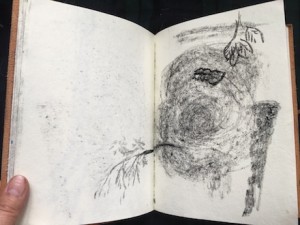

To the left of the path, a dark patch on the ground where a fire once stood between hemlock trees. Around it are stumps, seats for bottoms that left a while ago. I imagine who would have been here. A shiny purple corner of a chocolate sweet stands out on the edge of a pile of crumbly charcoal embers. I pick up a couple of handfuls and place them in a dog poo bag to make some ink later. I draw the face in the pile in my sketchbook, then walk on.

To the left of the path, a dark patch on the ground where a fire once stood between hemlock trees. Around it are stumps, seats for bottoms that left a while ago. I imagine who would have been here. A shiny purple corner of a chocolate sweet stands out on the edge of a pile of crumbly charcoal embers. I pick up a couple of handfuls and place them in a dog poo bag to make some ink later. I draw the face in the pile in my sketchbook, then walk on.

Everything has a language. the bark that’s been stripped pale in parts by deer, where trees have been felled or fallen, where light gets in through gaps to the forest floor is a patchwork of brown and green. It is all a language of life taking place. Everything has a language, whether it’s maths or fashion or culture, language is about interpreting, connecting, translating. The thing that is, and the language is how it can be read to understand it. Is there a language of the spirit? The language of signifiers, what about the language of the mind.

I see a tree that has no branches left, it looks as if it has been sliced at a diagonal half way up, and the bark is crumbling away. When you think of this, what comes to mind? Is it giving it’s last back to the earth, or is it in shock, struck. what comes to mind to you will be different to another person, possibly there will be similarities, but depending on how each person feels when they observe it, their experiences that are stored in their mind that remind them of something/someone/some feeling or objects. All this changes the experience of that tree. This idea isn’t new. When I make a drawing or a painting, because the work evolves from unconscious experiences, I get to witness something from experience form on the paper. It’s as if much of my conscious mind is on autopilot, that I can’t hear the underneath, the inner depths. This is maybe why the work I make isn’t pretty. It has relevations, alchemy. It shows me more than the name of something.

There is an issue of nouns. In recognising the name of something, we can stop looking at it. The curiosity of the shape of a flower can end if you pat yourself on the back for recalling it’s name. Language is a curious thing.

In this wood, a tall tree leans at 45 degrees onto a nearby beech, it is held in place only by it’s few uppermost branches. So much weight is held on so little. Time comes to mind. Time held in the lean of this tree, as if momentum waits to continue, as if the fall beckons.

My senses prick a little, an uneasy feeling. I walk on towards the sense of the discomfort and find another circle, this one is covered with sweet wrappers, cans of carling, fosters, heinekin, brown bottles without labels, a white bottle now filled with moss and mud. I walk on, more clearings. More circles. More bottles. If it wasn’t full of bottles, i would say that a shaman had been holding circle for workshops here. But the journeys here have been drunken ones. I don’t have a bag big enough to pick them up. Bong bottles, ripped cans. I carry Jack over the brambles then back up through the woods. How many hearts were joined and broken in these circles of teenage rites of passage? How many revisited? Was the young couple with the huskies and small child I passed on my way up the track outgrown drinkers from the past circles?

It’s only as I write this I make the connection between the small world found here today, and the larger issues we face. Humans leave traces, in the blindness of the dark and the drink and the rites of passage, nature bears witness, it has absorbed the stories of those young people in the woods. I read the language of the objects left behind, a sculptural story that evokes experiences, and a reminder to feel the vulnerability instead of numbing it when I encounter my next threshold.